2.2

We expected to see a clear statement from the Government clarifying:

2.3

The Government has stated that it intends to progress the SDGs "through a combination of domestic action, international leadership on global issues and support for developing countries". 7 We therefore expected to see an assessment of the extent to which national plans, sector strategies, and policies align with the 2030 Agenda, address the 17 SDGs and their targets, and identify gaps.

2.4

We expected clarity on how the SDGs are to be integrated across agencies and incorporated into their strategic planning. We expected the Government to provide clear guidance for agencies about how to consider the 2030 Agenda and the 17 SDGs and their targets when developing policy or other initiatives.

2.5

Since it adopted the 2030 Agenda, the Government has introduced several important national plans, legislation, policies, and initiatives that have some alignment with the 2030 Agenda, the 17 SDGs, and their targets. Some work has been carried out to see how the Living Standards Framework and the SDGs are aligned at a high level. In our view, this is not enough to properly understand the extent to which policies and initiatives contribute towards the SDGs, or to identify any gaps.

2.6

We have not seen evidence of the Government giving directives or guidance to agencies to integrate the SDGs, incorporate them into strategic planning, or assess existing or proposed policy against the 2030 Agenda and relevant SDG targets. This means that opportunities to strengthen the impact of policy on sustainable development outcomes might be missed.

2.7

In our view, the Government needs to more clearly describe its commitment to the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, including identifying what targets New Zealand will work towards. Until this is done, it will be difficult to show progress. The Government also needs to consider how it will do this work with Māori and in consultation with non-governmental stakeholders.

2.8

New Zealand is party to many multilateral international agreements. Some of these are legally binding under international law, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

2.9

The 2030 Agenda is not a legally binding agreement, meaning that it is up to the countries' governments to decide how they will give effect to their commitment to the 2030 Agenda and the 17 SDGs.

2.10

The Government has stated it is contributing to the SDGs "through a combination of domestic action, international leadership on global issues and support for developing countries". 8 However, nearly six years after it adopted the 2030 Agenda, the Government has not clarified how this will be achieved.

2.11

We would expect the Government to have indicated whether it intends to set specific SDG targets that New Zealand will work towards and, if so, in what areas. Where necessary, this could mean adding to or adapting the targets so they are more relevant to New Zealand.

2.12

It would be helpful if the Government clearly explained what it intends to achieve across the 17 SDGs by 2030, any necessary prioritisations or trade-offs that might be required, and how progress will be routinely monitored and reported.

2.13

Many stakeholders and agency staff we interviewed expressed a strong desire for the Government to clarify New Zealand's commitment to the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. As the 2030 Agenda spans multiple government terms, the hope was also expressed to us that all political parties would clearly support and commit to it.

2.14

We encourage the Government, working with Māori, and through meaningful engagement with stakeholders, to clarify New Zealand's commitment to implementing the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs.

| Recommendation 1 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Government clearly set out New Zealand's commitment to Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the sustainable development goals, including identifying which sustainable development targets New Zealand will aim to achieve by 2030. The Government will also need to consider how it will work with Māori to ensure that this commitment also upholds and reflects te Tiriti o Waitangi, and consult with relevant stakeholders. |

2.15

Given the breadth of the SDGs, we expected current national plans, sector strategies, and policies would address several SDGs or their targets. Our work indicates there is some alignment. In our survey (see paragraph 1.19), agencies considered current public sector initiatives to be "fairly" or "very" effective in preparing New Zealand to implement 11 of the 17 SDGs. However, there has been no comprehensive assessment of the alignment of national plans, strategies, and policies to the SDGs.

2.16

One of the initial stages of implementing the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs that the United Nations has identified involves reviewing current national plans, sector strategies, and policies to determine how much they already address the SDGs and their targets. This assessment can also identify any gaps where further work will be required to ensure that the SDGs are achieved and their targets are met by 2030. We did not see evidence of the Government carrying out a comprehensive assessment. Only two of the 12 agencies we surveyed said they had assessed the extent to which their policies and initiatives contribute to the 17 SDGs.

2.17

The Treasury has carried out a high-level assessment of how the Living Standards Framework and the SDGs align. 9 However, in our view, this is not enough to fully understand the extent to which New Zealand's policy settings and current or planned initiatives are aligned with and will contribute towards achieving the SDGs. We discuss the alignment of the SDGs with the Living Standards Framework in more detail in paragraphs 3.32-3.50.

| Recommendation 2 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Government carry out and publish a more comprehensive assessment of the extent to which policies and initiatives address the sustainable development goals and targets. |

2.18

There are tools available to assess the alignment of plans, strategies, and policies with the SDGs. The United Nations Development Programme has produced a Rapid Integrated Assessment toolkit to help with carrying out assessments. 10 We encourage agencies to use this or other tools to assess how national plans, strategies, and policies align with the SDGs and to identify any gaps.

2.19

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs' online tool, LinkedSDGs, could also help assess how much a plan, strategy, or policy addresses the SDGs. LinkedSDGs analyses a submitted document and extracts words related to sustainable development concepts. 11 The tool then links those words to specific SDGs, targets, and indicators.

2.20

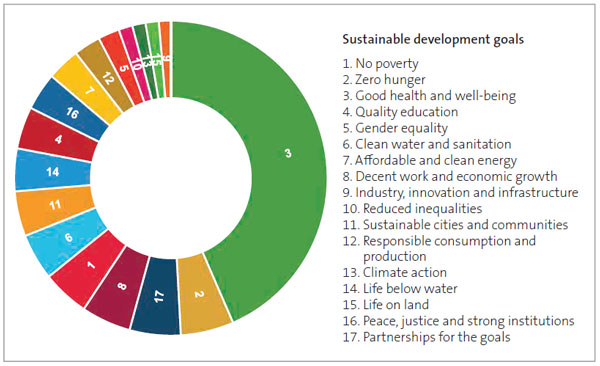

The results are presented visually and are interactive. Figure 3 shows some of the results when we used the tool on Our Plan: The Government's priorities for New Zealand. The size of each segment in the graph reflects the strength of alignment between that particular SDG and the document being assessed. Our Plan: The Government's priorities for New Zealand shows strongest alignment with SDG 3 (good health and well-being).

Source: Adapted from www.linkedsdg.org.

2.21

The visual tool might also help identify which SDGs have the weakest alignment with the submitted document, which could indicate gaps in the strategies, policies, or plans. When gaps are identified, governments are encouraged to consider what action is needed and what the barriers are.

2.22

The United Nations Development Programme has also developed the SDG Accelerator and Bottleneck Assessment tool. It sets out a step-by-step process to help identify potential accelerators (which move progress towards achieving the SDGs) and bottlenecks (where progress could be slowed) and appropriate interventions and solutions, and to produce an implementation and monitoring plan. 12 The bigger accelerators are those that allow for quick progress across a range of connected SDGs or targets, with minimal trade-offs for other SDGs.

2.23

The Government has introduced several important national plans, legislation, and initiatives that address some aspects of the 2030 Agenda.

2.24

In September 2018, the Government introduced Our plan: The Government's priorities for New Zealand – a 30-year plan to address complex challenges. This time frame is consistent with the 2030 Agenda's consideration of both present and future needs, and the plan intends to provide for an economy that protects the environment and ensures that all New Zealanders benefit from economic growth.

2.25

The 2030 Agenda was based on similar intentions, with a focus on social, environmental, and economic development. However, we did not see evidence that the Government has assessed how much of the plan's priorities and associated actions align with the SDGs and their targets.

2.26

The 2019 Wellbeing Budget introduced priorities that were focused on improving the well-being of people, communities, and natural resources, as well as on economic growth. Like the 2030 Agenda, the 2019 Wellbeing Budget acknowledged that effective short- and long-term decision-making requires social, environmental, and economic implications to be considered together.

2.27

Budget bids were assessed on how they affected social, environmental, economic, and cultural factors and long-term outcomes. The 2019 Wellbeing Budget included a well-being outlook report for New Zealand as well as the usual economic and fiscal outlooks. Recent legislation encourages a long-term focus for some aspects of sustainable development.

2.28

To ensure that future government budgets remain focused on well-being, the Public Finance (Wellbeing) Amendment Act 2020 requires budgets from 2021 to be guided by objectives that support long-term social, environmental, economic, and cultural well-being. The Amendment Act also introduced a requirement for the Treasury to produce a report about the state of well-being in New Zealand at least every four years. The first report is to be presented before the end of 2022.

2.29

The Government has acknowledged that quicker progress is needed to achieve meaningful improvement in the well-being of New Zealanders and that single agencies cannot resolve many of the country's long-standing complex issues. The Public Service Act 2020, which replaced the State Sector Act 1988, aims to establish a more flexible and collaborative public service, strengthen the Crown's relationships with Māori, and deliver better outcomes for New Zealanders.

2.30

The 2030 Agenda emphasises that eradicating poverty is fundamental for sustainable development.

2.31

Amendments in 2018 to the Children's Act 2014 13 require the Government to create a well-being strategy for children, with a particular focus on children with greater needs. This is aligned with the 2030 Agenda's focus on vulnerable communities. The 2018 amendments also require an action plan for the strategy, and the Government must report annually on its progress, including progress for children with greater needs.

2.32

The strategy, called the Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy, notes that its implementation will strengthen New Zealand's commitment to the SDGs. However, it does not describe how its intended outcomes align with relevant SDGs and targets.

2.33

The Child Poverty Reduction Act 2018 requires successive governments to set targets to reduce child poverty. The first targets, announced in 2019, included reducing by more than half the proportion of children living in low-income households and in material hardship by 2027/28. These targets appear to be aligned with the SDG target to halve the proportion of people living in poverty by 2030. 14 The Act requires Statistics New Zealand to report annually on progress towards the targets and on supplementary child poverty measures. These reports include disaggregated data for Māori children and for other groups of children, where suitable data is available.

2.34

The United Nations has acknowledged that the Paris Agreement, which is part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, is integral to achieving the SDGs. 15

2.35

In 2019, amendments to the Climate Change Response Act 2002 established climate change reduction obligations and targets for New Zealand. This contributes to the global effort under the Paris Agreement to "limit the global average temperature increase to 1.5° Celsius above pre-industrial levels". 16

2.36

The Climate Change Response Act has introduced mandatory emissions budgets to help New Zealand meet its 2050 targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and align with global efforts under the Paris Agreement. The Government must implement climate change mitigation and adaption policies and strategies to meet the current emissions budget.

2.37

The Climate Change Commission (the Commission) was created through the 2019 amendments to the Climate Change Response Act. The Commission provides independent and expert advice on mitigating, and adapting to, the effects of climate change. This includes producing a national climate change risk assessment at least every six years and monitoring progress towards the emissions reduction and adaptation goals. Consistent with the principles of the 2030 Agenda, the Commission considers the economic, social, environmental, and cultural effects of climate change, and how these effects are distributed across society, including vulnerable groups, Māori, and future generations.

2.38

The Commission published Ināia tonu nei: A low emission future for Aotearoa in May 2021, providing its advice and recommendations for the Government's first three emissions budgets and emissions reduction plans. The report notes that New Zealand's 2050 greenhouse gas targets are unlikely to be met under current government policies. The Government is to provide its response by 31 December 2021.

2.39

The 2030 Agenda emphasises the importance of involving local government and other organisations in implementing the SDGs.

2.40

The Local Government (Community Well-being) Amendment Act 2019 amended the Local Government Act 2002 by reinstating the purpose of councils to promote social, economic, environmental, and cultural well-being (the four well-beings) of their communities by using a sustainable development approach.

2.41

Consistent with the 2030 Agenda, the 2019 amendments included the principle that councils should consider the potential effects of their decisions on each of the four well-beings and resolve any conflicts between these well-beings openly and transparently. The amendments also require councils' long-term plans to identify any significant negative effects that their activities might have on the four well-beings, and that any identified effects be described in councils' annual reports.

2.42

The Government Procurement Rules (4th edition), which came into force in 2019, require agencies to consider, where appropriate, broader environmental, social, economic, and cultural outcomes that can be attained from their procurement processes. 17

2.43

These rules also require agencies to consider the potential costs and benefits to society, the environment, and the economy as well as the cost of their procurement.

2.44

To assess the corporate documents of the 12 agencies we surveyed, we looked at the current long-term plans (that is, the agencies' strategic intentions, or four-year plans), 2020 briefings to incoming Ministers, and 2019/20 annual reports for any references to the SDGs. The Public Service Act 2020 now requires government departments to produce independent long-term insights briefings. 18 However, the first of these briefings was not available at the time of our review.

2.45

There were limited references to the SDGs in the agencies' corporate documents. SDGs were referenced in only two long-term plans, four briefings to incoming Ministers, and four annual reports. Although this does not necessarily mean the agencies are not addressing issues relevant to the SDGs, we would expect reference to the SDGs if they were a key consideration.

2.46

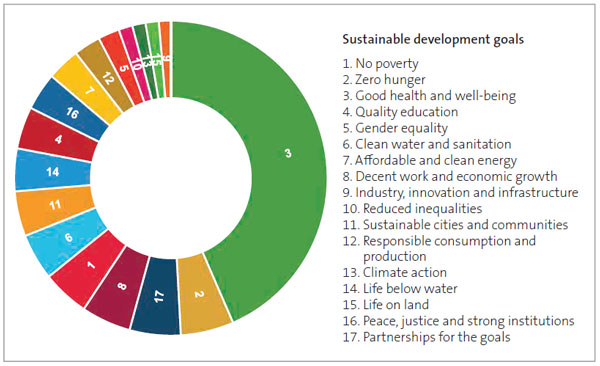

In our survey (see paragraph 1.19), the 12 agencies were asked to consider how well a particular SDG was reflected in their agency's priorities and policy development, as well as at a national level (see Figure 4). Some agencies were asked about more than one SDG.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

2.47

Eight of the 12 agencies considered that current public sector initiatives have prepared New Zealand to implement the particular SDG or SDGs they were asked about. Altogether, the agencies provided us with more than 120 examples of policies or initiatives that they considered aligned with one or more of the SDGs. Our review of the examples provided by the Ministry for Social Development for SDG 10 (reduced inequalities) supports this (see Appendix 1).

2.48

Many stakeholders considered there to be generally a low level of awareness of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs in central government.

2.49

Several stakeholders we spoke with are national-level advocates for some of the vulnerable groups that the 2030 Agenda states should "not be left behind". For many of these advocates, the SDGs have not often or have never been discussed in their interactions with agencies. We discuss stakeholder engagement in Part 4.

2.50

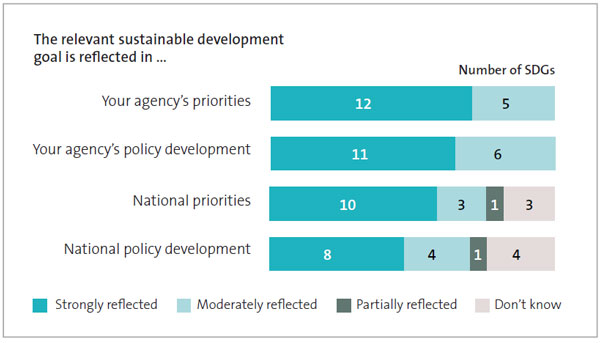

The 2030 Agenda states the importance of governments incorporating the SDGs into national policy. However, many stakeholders felt that the SDGs were used mostly as a framework to report back to the United Nations, rather than a tool to inform policy and support monitoring and reporting. The agencies we surveyed acknowledged that not many of the policies and initiatives they provided to us explicitly refer to the SDGs or their targets (see Figure 5). We recognise that this does not necessarily mean that those policies and initiatives do not align with the SDGs.

Note: The surveyed agencies were asked to identify the policies and initiatives that they considered support the SDG(s) they were asked about. For each policy or initiative they identified, they were asked whether it refers to the SDG and included any SDG targets.

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

2.51

We understand that the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs are not the only drivers for policy decisions. However, the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs could still be useful when policy is being developed. Organisations outside government have used the SDGs to inform their strategies and initiatives. We discuss some of these examples in paragraph 4.15 and Figures 8 and 10 in Part 4.

2.52

We also asked agencies whether policies supporting a particular SDG have been assessed to see how they might affect the achievement of other SDGs. For 12 of the 17 SDGs, there had been no work on this, or agencies were not aware of whether work had been done. The United Nations has endorsed a tool developed by the Millennium Institute that helps identify the likely effect proposed policy initiatives will have on the 17 SDGs. The Integrated SDGs Simulation Tool analyses components of a proposed policy or initiative and then shows the likely effects on the 17 SDGs.

2.53

Many stakeholders we interviewed commented that SDGs were often referred to in New Zealand's international policy. Our review of the international development examples provided by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Trade for SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals) supports this (see Appendix 2).

2.54

Concerns were raised with us that other international agreements integral to successfully implementing the SDGs might also not be explicitly considered in policy development. The Chief Human Rights Commissioner told us he is concerned that there are several important human rights treaties that are not taken into account in relevant national and local policy-making processes.

2.55

The Children's Commissioner has also made similar and repeated calls for the principles and provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, particularly for vulnerable children, to be incorporated into policy. We agree with the Chief Human Rights Commissioner and the Children's Commissioner that the implications of our international agreements should be appropriately reflected in policy development, and progress should be monitored and reported.

2.56

The United Nations has reiterated the importance of remaining focused on the SDGs during the Covid-19 recovery and ensuring that any progress that had been made before Covid-19 is not undone. Many of the stakeholders we spoke with shared concerns about the effects of Covid-19 on implementing the SDGs.

2.57

Many of the groups that the 2030 Agenda defines as vulnerable have been disproportionately affected by Covid-19. The principle of "leaving no one behind" is therefore even more relevant in the Covid-19 recovery environment.

2.58

With the drive for rapid recovery, some stakeholders we spoke with felt that policies and initiatives for the Covid-19 recovery are less likely to consider the impacts or opportunities across the three dimensions of sustainable development (social, environmental, and economic). There was a view that, while the environmental and economic dimensions of sustainable development were often considered, there was not as much focus on the social dimensions.

2.59

However, New Zealand's statement to the United Nations' 2020 High Level Political Forum for Sustainable Development acknowledges the particular relevance of the SDGs at this time. The statement also confirms that "New Zealand is committed to adopting a wellbeing approach that reflects the SDGs as we seek to respond, recover and rebuild from Covid-19". 19 We have not assessed whether the SDGs are reflected in the Covid-19 response initiatives that had been implemented at the time of our fieldwork. However, one example provided to us was the $36 million Community Capability and Resilience Fund. The fund is intended to support community groups' Covid-19 response and recovery initiatives that are focused on priority populations, including initiatives to build economic capability.

2.60

We did not see evidence of the Government issuing any directives or guidance to agencies to integrate the SDGs across agency work programmes, incorporate them in their strategic planning, or assess existing or proposed policy against the 2030 Agenda and the SDG targets. In our view, this means that opportunities to strengthen the quality of policy or other initiatives and their effect on sustainable development outcomes might potentially be missed.

2.61

In November 2019, the Treasury published Information on applying a wellbeing approach to agency external planning and performance reporting. This fact sheet gave guidance for agencies on how a well-being approach could be incorporated into their strategy, planning, and performance reporting processes. In our view, this fact sheet could include the SDGs. The Treasury has told us it will include reference to the SDGs in the next update of the fact sheet.

2.62

Currently, the Living Standards Framework is the policy assessment tool that is most aligned with the SDGs. Developed in 2011 and last revised in 2018, the Living Standards Framework was designed to improve assessment of the extent to which policies consider sustainable growth and improved living standards, and the effect on both current and future well-being.

2.63

Consistent with the 2030 Agenda's principles, the Treasury uses the Living Standards Framework to consider the effect of policy options on current and future economic, social, environmental, and cultural well-being domains. It is designed to help identify potential trade-offs and interactions across the domains and how different demographic and geographic groups are likely to be affected.

2.64

Agencies have used the Living Standards Framework alongside other tools and information to inform their advice to Ministers about spending priorities and proposals, including how the initiatives in their 2019 and 2020 budget bids would contribute to improved living standards. Although the Treasury told us that agencies are increasingly considering living standards, the Living Standards Framework is not yet routinely applied across central government's policy and initiatives development work.

2.65

Although there is some alignment, the Living Standards Framework does not cover all the SDGs. The Treasury has looked at how the Living Standards Framework's 12 domains of current well-being and its four capitals that are key for future well-being map to the 17 SDGs.

2.66

The majority of the SDGs mapped to one or more of the well-being domains and capitals. However, the Treasury acknowledges that the links between some of the SDGs and well-being domains or capitals are more ambiguous than others. For example, the well-being domain "housing" corresponds to the much broader SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities). Six SDGs are focused on the environment, whereas the Living Standards Framework has only one well-being domain on the environment and a "natural" capital.

2.67

There is guidance on developing Cabinet papers that asks agencies to consider the implications of their policies for some matters relevant to the SDGs, including human rights, the climate, and implications for a range of different population groups. This guidance also directs agencies to look to the Living Standards Framework dashboard and Ngā Tūtohu Aotearoa – Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand for data to support their assessment.

2.68

However, by directly considering the general principles of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs and their targets during strategic planning and the early stages of policy development, there are further opportunities to ensure that policies have:

2.69

In our view, the Government needs to set clear expectations for agencies on how to integrate and incorporate the SDGs in their strategic planning, and consider the 2030 Agenda's principles and the SDG targets that New Zealand is working towards in their policy work.

2.70

There are also other tools to help inform policy development – for example:

2.71

In our view, the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs could be mentioned more explicitly in the guidance. If the Government clarifies which targets New Zealand intends to focus on, this could also be incorporated. This would assist the Government in articulating its contribution to the SDGs and could provide a basis to determine which initiatives could be included in reporting on progress – for example, in the next voluntary review.

2.72

Alternatively, the Living Standards Framework could be further developed to more explicitly reference the principles of the 2030 Agenda, the SDGs, and SDG targets that are relevant to New Zealand, and be consistently applied across policy development work. We understand that the Treasury intends to review and update the Living Standards Framework in 2021.

| Recommendation 3 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Government set clear expectations for how the sustainable development goals are to be incorporated in government agencies' strategic planning and policy work, and how agencies are expected to work together to ensure an integrated approach to achieving the goals. |

2.73

Six of the 12 agencies we surveyed commented that funding to implement an SDG is provided through the budget appropriations for initiatives that happen to align with a particular SDG.

2.74

Through our survey, it was reported that some work was under way to determine the resourcing required to implement four of the SDGs.

7: New Zealand Government (2019), He waka eke noa – Towards a better future, together: New Zealand's progress towards the SDGs 2019 , page 6.

8: New Zealand Government (2019), He waka eke noa – Towards a better future, together: New Zealand's progress towards the SDGs 2019 , page 6.

9: The Living Standards Framework, developed independently of the Government of the day, is designed to help improve policy advice for sustainable growth and improving living standards, including considering the impacts of policy options on both current and future well-being.

10: The United Nations Development Programme Rapid Integrated Assessment and its tools can be accessed at www.undp.org.

11: The LinkedSDGs tool can be accessed at www.linkedsdg.org. We have not verified the accuracy of this tool, but it is endorsed by the United Nations.

12: The United Nations Development Programme SDG Accelerator and Bottleneck Assessment tool can be accessed at www.undp.org.

13: The Children's Amendment Act 2018.

14: The full wording of the SDG 1.2 target is "by 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions".

15: The Paris Agreement entered into force on 4 November 2016 and came into effect from 2020. It is the current international accord for climate change. As a signatory to the agreement, New Zealand is required to have an emissions reduction target, regularly report on progress towards the target, plan for New Zealand's climate change adaptation, and support that of developing countries.

16: Section 5W(a) of the Climate Change Response Act 2002.

17: The Government Procurement Rules apply to government departments, New Zealand Police, the New Zealand Defence Force, and most Crown entities for procurement worth more than $100,000 or $9 million for new construction. Wider State sector and public sector agencies are encouraged to have regard to the Rules as good practice guidance.

18: The Public Sector Act 2020 requires government departments to produce an independent long-term insights briefing at least every three years, providing information on the medium- and long-term issues and opportunities that New Zealand faces and policy options to respond to these. Public consultation is to be carried out on the topics to be included in the briefings and then on the draft briefings. All briefings will be made publicly available. The first briefings will be presented to Parliament in June-July 2022.

19: New Zealand Permanent Mission to the United Nations (2020), High Level Political Forum for Sustainable Development 2020: New Zealand statement, page 2, at sdgs.un.org.